NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

HISTORICAL NEWSPAPER DATA:

A RESEARCHER’S GUIDE AND TOOLKIT

Brian Beach

W. Walker Hanlon

Working Paper 30135

http://www.nber.org/papers/w30135

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

June 2022

We thank James Feigenbaum, Andy Ferrara, Kris Mitchener, Sebastian Ottinger, Paul Rhode,

Martin Saavedra, and Tianyi Wang for their many useful comments. We thank Christopher Sims

for excellent research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been

peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies

official NBER publications.

© 2022 by Brian Beach and W. Walker Hanlon. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to

exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit,

including © notice, is given to the source.

Historical Newspaper Data: A Researcher’s Guide and Toolkit

Brian Beach and W. Walker Hanlon

NBER Working Paper No. 30135

June 2022

JEL No. N0

ABSTRACT

Digitized historical newspaper databases offer a valuable research tool. A rapidly expanding set

of studies use these databases to address a wide range of topics. We review this literature and

provide a toolkit for researchers interested in working with historical newspaper data. We provide

a brief description of the evolution of historical newspapers, focusing on aspects that are likely to

have implications for the design of empirical studies. We then review the main databases in use.

We also discuss some key challenges in using these data, most importantly the fact that even the

most extensive datasets contain only a selected sample of the universe of historical newspaper

articles. We offer tools for evaluating the comprehensiveness of available newspaper datasets,

show how to assess potential identification concerns, and suggest some solutions.

Brian Beach

Department of Economics

Vanderbilt University

VU Station B, Box #351819

2301 Vanderbilt Place

Nashville, TN 37235

and NBER

W. Walker Hanlon

Department of Economics

Northwestern University

2211 Campus Drive, 3rd floor

Evanston, IL 60208

and NBER

A data appendix is available at http://www.nber.org/data-appendix/w30135

1 Introduction

The emergence of large-scale digitized and searchable historical newspaper databases

has expanded both the tools that economists can employ to study historical settings as

well as the set of questions that can be asked. Before this arrival, researchers typically

extracted information from microfilm or online archives of specific newspapers. This

labor-intensive process meant that a researcher had to know what to search for and

where to search. This was still a useful approach, forming the basis of many price

series and other studies.

1

But with digitized scans and optical character recognition

(OCR) in particular, a researcher can now conduct keyword searches that effectively

sift through millions of articles in a matter of seconds. This search innovation, along

with large and continuously expanding archives, allows researchers to explore a wide

variety of topics and settings, including many that are difficult to approach using

other data sources, such as government statistics.

This rich potential is on display in a number of recent papers. To cite just a few

examples, searches of digitized large-scale newspaper databases have formed the basis

of several new and local measures of racial and ethnic discrimination (Bazzi et al. ,

2021; Fouka, 2019; Ferrara & Fishback, Forthcoming) as well as measures of support

for the U.S. Civil Rights Movement (Kuziemko & Washington, 2018; Calderon et al.

, Forthcoming). Newspapers also offer a useful source of variation in the salience

of news events. Some use variation in reporting of events, such as Albright et al.

(2021) in their study of the economic consequences of the Tulsa Race Massacre. An

1

This approach has a long history in economics, particularly among those studying financial

and commodity markets. These papers are made possible by reporting of prices in newspapers as

well as the existence of specialized periodicals such as Lloyd’s List. One non-financial paper that

received a lot of press recently is, Markel et al. (2007), which uses newspaper archives to supplement

other sources to identify both the existence and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on

mortality during the 1918 influenza pandemic.

1

alternative approach is offered by Beach & Hanlon (Forthcoming), which studies the

impact of a prominent trial that promoted family planning by comparing fertility

responses in areas where a newspaper opened just before the trial, in time to report

on it, to similar areas where newspapers instead opened just after the trial. Newspa-

per archives have also been used to identify a range of treatments, including school

closures during the 1918 influenza pandemic (Ager et al. , Forthcoming), exposure

to racist propaganda (Ang, 2020; Esposito et al. , 2021), and technology adoption

(Caprettini & Voth, 2020).

While historical newspapers have enormous potential as a research tool, there

are also important challenges that must be faced. This article aims to facilitate the

growing use of historical digitized newspapers by providing researchers with tools that

allow them to use this data resource more easily and effectively.

Section 2 provides a brief overview of the historical development of newspapers,

with a particular focus on elements that are likely to be relevant for researchers using

digitized newspaper databases. Historical newspapers differed in important ways from

those that we are familiar with today. Newspapers changed as production technology

improved, demand conditions changed, and market structures evolved. Their physical

structure and appearance was altered, they changed the mix of news and opinion that

they printed, the methods for gathering news improved, the frequency of publication

increased, etc. A number of these changes have implications for researchers. We

highlight key patterns and issues, while providing citations to literature by media

historians that researchers can use to dig deeper into newspaper features from their

setting of interest.

In Section 3 we highlight the wide range of topics where newspaper data can

be useful as well as the many different ways that newspaper data are being used.

2

Newspapers are used to measure key outcomes of interest, as indicators of treatment,

and even as instruments that can improve the precision of other noisy treatment

measures. In some studies, newspapers are themselves the outcome of interest, while

in others they act as a mechanism through which effects are transmitted. This section

aims to provide key references for researchers working in this area, as well as to

highlight the many different ways that newspaper data can be used moving forward.

One feature of the existing literature, mainly within the U.S. context, is that

studies draw from a diverse set of newspaper databases. In Section 4, we review and

assess the primary databases used by existing studies and discuss some databases

which have not yet been extensively used. We also provide an assessment to help

guide researchers to the most extensive database available in any particular context.

To facilitate our assessment of digitized newspaper databases, we also discuss

available data from newspaper directories. These directories, typically aimed at con-

necting advertisers with papers, are available starting in the middle of the nineteenth

century, at least for the U.S. and U.K. Directories provide a fairly comprehensive list-

ing of existing newspapers along with other useful information, such as their political

affiliation, whether they were a general paper or focused on a specific topic such as

business, the price and frequency of publication, etc. Directory data have been used

by a number of existing studies, such as Petrova (2011), Gentzkow et al. (2011),

Gentzkow et al. (2014a), and Cag´e (2020). However, only a few studies have used

directory data together with digitized historical newspaper archives. We argue that

directory data can provide a valuable complement to digitized newspaper data. For

example, directory data can be used to assess the comprehensiveness of the different

digitized newspaper archives as well as for identifying the characteristics of the papers

that predict selection into those archives.

3

To demonstrate the value of using directory data alongside digitized newspaper

archives, we have digitized a set of directory data for the U.S. in 1910 and the U.K.

in 1895 and matched them to the main newspaper databases used by studies focused

on those settings. In both settings, we find that existing newspaper directories cover

a fraction of the newspapers present in any given setting. In the U.K. in 1895, for

instance, only 30% of provincial newspapers appear at least once in the British News-

paper Archive. The fraction is 47%, if we focus only on daily papers, which tended

to be more important, established, and urban. In the U.S., we conduct a similar

exercise using the 1910 directory and the most extensive U.S. newspaper database

for that period, Newspapers.com, which is the source used by the majority of U.S.

studies. Here we see wide variation in coverage rates across states. Newspapers.com

holds 69% of all of the papers published in Nebraska, 36% of those in Alabama, but

just 8.6% of those in Washington State, and 0.02% in Massachusetts. Coverage is

only slightly higher for daily papers.

The implication of these results is that accounting for the selection of papers into

existing newspaper datasets is likely to be important. Given this, in Section 5 we

provide several methods to help researchers deal with selection concerns when using

historical newspaper data. For example, one simple approach is to divide raw counts of

search “hits” by appropriate denominators so that analyses are based on hits relative

to the underlying distribution of newspapers. We also discuss how directory data can

be used to identify and adjust for selection patterns that may be generating bias. In

particular, using the information about each newspaper available in the directories,

we can identify dimensions along which the papers available in newspaper archives

have been selected and assess whether this selection is likely to be problematic for a

particular analysis approach.

4

Directory data can also allow researchers to implement stronger identification

strategies. One example is provided by Beach & Hanlon (Forthcoming) where news-

papers acted as a treatment mechanism that exposed people to news about an im-

portant event, the Bradlaugh-Besant trial of 1877. That paper exploits information

in the directories on the location and year of establishment of papers. Using this

information, they compare locations where newspapers opened just before the trial,

and so helped expose locals to news about the trial, to similar locations where a paper

happened to instead open just after the trial.

Together, these elements aim to make digitized historical newspaper data more

accessible and usable for economics researchers, while also helping to improve the

quality and standardize the practices applied when using these data sets.

2 Newspaper Origins and Development

The invention of the movable type printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the

fifteenth century opened up the possibility for printing regular news, but it would

take many centuries for the modern newspaper to develop. Over the course of this

evolution, newspapers would be influenced primarily by three forces: government reg-

ulations, technology development, and economic conditions determining the demand

for news and advertising. These factors influenced the physical form of newspapers,

the information they contained, sources of revenue, and the overall structure of the

newspaper market. Each of these has implications for the information that can be

gleaned from digitized newspaper data and the ways in which that information should

be analyzed.

Early newspapers emerged from the corantos that began to be published in Conti-

5

nental Europe at the end of the sixteenth century, starting with the Mercurius Gallo-

beligus published in Cologne in 1594.

2

These compendiums of recent news, published

at various intervals from biannually to weekly, spread throughout Western Europe

over the course of the sixteenth century.

The early history of newspapers is often referred to by media historians as the

“printer’s newspaper” period, because newspapers were produced by printers as just

one (often small) part of their business.

3

For much of this period, which stretched into

the eighteenth century, newspapers did not employ a dedicated news-gathering staff.

Instead, papers focused heavily on opinion or on news obtained through letters or

other sources. Printed material during these early years remained expensive, and so

newspapers were confined to wealthy readers. Government support, regulation, and

often repression, played a crucial role in determining the behavior of papers in most

countries. In Britain, for example, the government of Sir Robert Walpole (1721-1742)

spent thousands of pounds from the Treasury setting up newspapers or influencing

their content.

4

This led to papers that were largely mouthpieces for the government

or other powerful patrons. Naturally, these features influence the information we can

expect to glean from the (relatively rare) set of digitized articles available from this

early period.

The eighteenth century saw newspapers undergo important changes. In Britain,

the loosening of state control of newspapers following the lapsing of the Licensing Act,

in 1695, led to a rapid expansion in the industry. Newspapers continued to receive

revenue from the state or other powerful sponsors in exchange for political support,

but advertising was growing as a source of revenue. As advertising became more

2

Williams (2010), p. 40.

3

Barnhurst & Nerone (2001).

4

Williams (2010), p. 65.

6

important, it allowed newspapers more independence, while also pushing them toward

taking more neutral political positions. That was particularly true for provincial

papers outside of the larger cities, which operated in markets that were too small to

support market segmentation.

This era also saw the emergence of direct reporting, by papers such as Daniel

Defoe’s Weekly Review, as well as dedicated journalists. However, these remained

concentrated in larger cities such as London. In more provincial locations, or the

American colonies, busy printers rarely had the time for extensive reporting or editing.

As censorship eased, at least in some countries, governments sought to control the

newspaper press by imposing heavy stamp taxes. These affected the format of papers,

which sought to convey the maximum amount of information for the minimum tax

rate, as well as keeping papers confined to serving wealthier readers. In terms of

form, eighteenth-century newspapers remained densely printed with few headlines, a

format that would continue through the late nineteenth century.

As the middle of the nineteenth century approach, newspapers began evolving

from the era of the “printer’s newspaper” to that of the “editor’s newspaper.” By

the middle of the century, powerful editors–people like John Delane at The Times–

emerged as independent personalities shaping the content of their papers and man-

aging their growing news-gathering organizations. Technological change played an

important role in this shift. The falling cost of paper in the early 19th century, due

in part to mechanized papermaking and in part to falling taxes, and technological

innovations such as the steam-powered press (1814) and multiple-cylinder stereotype

printing (1827), reduced the cost of producing newspapers.

5

As costs fell, newspapers

were able to expand circulation and increase advertising, in turn allowing newspapers

5

Williams (2010), p. 76.

7

to gain independence.

The timing of the emergence of a more independent and “informative press” varied

across countries. In the United States, for example, Gentzkow et al. (2006) argue

that the informative press emerged sometime between 1870 and 1920. As late as 1870,

most papers were openly partisan and charged language frequently appeared in print.

Among larger cities, independent newspapers only accounted for 26% of circulation

in 1870, but by 1920 73% of circulation came from independent newspapers. This

change was driven mostly by the entrance of new independent papers as opposed to

existing papers abandoning their political affiliations.

While competitiveness is part of the story, declining production costs and increas-

ing population changed the scale of the industry, which also altered publishing incen-

tives. Petrova (2011) links the emergence of independent papers specifically to the

increasing availability of advertising revenues, which allowed newspapers to survive

without the sponsorship of political parties. Expanding revenues also allowed news-

papers to undertake more direct reporting. This was facilitated by the development

of Isaac Pitman’s universal shorthand in the 1840s.

Cheaper newspapers opened up the possibility of serving a broader population

of readers, including those in the working class. In Britain, this led to the emer-

gence of an “unstamped” (i.e., illegal) radical press, particularly in the 1830s. These

unstamped papers, such as the Northern Star of Leeds, had circulations that were

as large as, and may have exceeded, more established stamped papers. These new

radical papers differed in important ways from the more established variety. For ex-

ample, advertisers were less interested in speaking to working class readers in the

early nineteenth century, who had limited purchasing power, so subscriptions made

up an important part of the revenue for these papers. Eventually, the reduction in

8

stamp taxes in the middle of the nineteenth century pushed the radical papers to

become stamped, but the existence of many unstamped radical papers in the first

half of the nineteenth century has important implications for researchers working in

that period. Being illegal, such papers are less likely to have survived and to have

found their way into historical newspaper databases, or onto advertising directories.

One important consequence of the falling cost of producing papers was an increase

in daily papers, in place of papers published one, two, or three times a week. Major

cities commonly had multiple daily papers by the late nineteenth century, and mid-

sized towns often had one. But in smaller towns and villages the vast majority of

papers were published at a lower frequency well into the 20th century. In Britain in

1895, for example, the Newspaper Press Directory, which we discuss more later, lists

136 daily papers published outside of London (including those printed 5 or 6 days a

week), 1,161 weekly papers, as well as 108 published twice a week and 13 published

three times a week. In the 1910 U.S. newspaper directory, we observe 2,376 daily

papers and 16,447 published one, two, or three days a week. The implication here

is that a study focused on nineteenth century daily papers will overlook the vast

majority of newspapers, particularly outside of major cities.

Another major change in the middle of the century was the introduction of tele-

graphic news. Wang (2019) describes how the 1840s expansion of the telegraph in

the U.S. altered the content of local newspapers, which began printing more national

news. He shows that these changes had important consequences, such as raising

political participation. The completion of the Trans-Atlantic telegraph and the Indo-

European connection, in the 1860s, likely had a similar effect on coverage of foreign

news. During the Crimean War, in the 1850s, reporters such as William Howard Rus-

sell of the Times provided dispatches from the front through long and detailed letters

9

that took days or weeks to reach printers in Western Europe.

6

By the 1870 Franco-

Prussian War, the widespread use of the telegraph meant that readers in Britain and

the U.S. were able to read in their morning paper about the events of the previous

day. Telegraphic news affected both the content and the form of newspapers. Na-

tional and foreign news became a cornerstone of newspaper content, with circulation

surging during major foreign events. The necessarily short nature of telegraphic news

meant that it was inevitably published as lists of brief snippets.

The telegraph was also intertwined with the rise of press services, such as Reuters

(UK), the Associated Press (US), the Press Association (UK), and United Press

(US). These allowed local papers to obtain high-quality national and foreign reporting

directly, overcoming their dependence on the major city papers. This ushered in the

heyday of local papers in the mid-nineteenth century, though in places like the U.K.

local papers also faced rising competition from the major national papers as rapid

railroad mail delivery expanded.

The rise of these press associations has potentially important implications for

studies using digitized newspaper databases. By providing standardized content used

by many papers, the activities of wire services may have a substantial influence on the

results obtained from searches of digitized newspaper articles. One has to consider

whether obtaining, say, one hundred hits for the same AP article published by many

local newspapers should be treated the same way as one hundred independently pro-

duced articles. The associations, particularly the Associated Press, also influenced

the content of articles, as highlighted recently by Djourelova (2021).

The next major step in the evolution of the newspaper industry was the rise of the

“publishers paper.” This process began in the U.S. with the arrival of commercially

6

Williams (2010), p. 114.

10

successful and highly profitable mass market papers, spreading from there to Britain

and Europe.

7

This evolution was due in part to the growth of disposable income and

literacy among the working class. This, together with technological improvements–

such as the rotary press in the mid-nineteenth century and the linotype printing

machine, invented in 1884–that continued to reduce the cost of printing, as well as

technology that allowed papers to expand their content by adding illustrations and

eventually photographs, led to the expansion of mass market newspapers. The high

fixed costs and lower marginal costs, together with rapidly growing demand, led to

changes in both the structure of the industry and the physical form and content of

papers. Power shifted from editors to publishers, such as William Randolph Hearst

and E.W. Scripps in the U.S. or Alfred Harmsworth (Lord Northcliffe) in the U.K.

Control of these sprawling newspaper empires allowed publishers to exercise control

along many dimensions, including printed content.

Over time, the dense, many-columned format and lengthy articles of Victorian

newspapers, an “undigested, complex barrage on the page” (Barnhurst & Nerone,

2001, p. 17) would give way to shorter, snappier articles with prominent titles.

Barnhurst & Nerone (2001, p. 195) chart the decline in the number of front page

items and articles during this period. In a sample of American papers, they observe

an average of 50 front page items including nearly 25 articles in 1885. By 1915, this

had declined to just over 20 items and around 15 articles.

Starting sometime in the interwar period, media scholars identify the onset of

modernization in newspapers, as they began to take forms that we would be more

familiar with today.

8

Rising competition between newspapers likely played a role

in driving them to be more consumer friendly, as did the increasing threat from

7

Williams (2010), p. 126.

8

See, e.g., Barnhurst & Nerone (2001), p. 20-21.

11

other media, starting with cinema, and then radio and television. These changes

were most visible on the front page, which became the paper’s “display window” and

a “functional map...of the day’s news from top to bottom” (Barnhurst & Nerone,

2001, p. 204). Papers such as the New York Tribune in the U.S. and Daily Express

in the U.K. emphasized the importance of layout and design, leading to a “slick,

synthetic product” (Williams, 2010, p. 156) that bore little resemblance to a Victorian

newspaper. The defining features of modernist papers–fewer items, more space, larger

headlines, and a clear hierarchy–reached their apex in papers such as USA Today,

founded in 1982.

We have now charted, in an abbreviated fashion, the broad historical evolution

of the newspaper. This evolution encompassed changes in design, content, editorial

control, market structure, and many other factors that are relevant for researchers

using historical digitized newspaper data. Our hope is that this review offers a starting

point for researchers as they delve more deeply into the period-specific conditions

under which the newspaper content they wish to study was generated.

3 Applications

3.1 Digitized newspaper article data

A rapidly-expanding set of papers that use digitized newspaper data illustrates the

many ways in which newspaper data can contribute to economic studies. There are

several ways that we could organize or classify work in this area. One dimension is

topic, which varies widely across studies. One could also focus on the type of newspa-

per content that is being used; differentiating, for example, between studies focused

on article content and those that use information gleaned mainly from advertisements.

12

A third potential approach to classification, and the one that we adopt, focuses on

the function played by newspaper data within a study. We focus primarily on this

aspect in our discussion because the function of the data within an analysis is likely

to play a primary role on the methodological issues encountered.

The most common use of newspaper data in economic studies is as a way to

measure some type of treatment in order to construct a key explanatory variable.

Studies on the 1918 influenza pandemic, for instance, often rely on newspaper data

to evaluate the impact of local interventions such as mask mandates, bans on public

gatherings, or school closures (Markel et al. , 2007; Ager et al. , Forthcoming; Velde,

2022).

9

Fouka (2019) and Ferrara & Fishback (Forthcoming) use newspapers to iden-

tify U.S. areas with stronger anti-German sentiment in the wake of WWI. Ang (2020)

and Esposito et al. (2021) use newspapers to identify screenings of the blockbuster

racist movie “The Birth of a Nation” and then study the movie’s impact on several

outcomes. Feigenbaum & Gross (2021) use newspaper data to track the diffusion of

mechanical switching technology in the U.S. telephone industry in their study of the

impact of automation on workers. In the U.K., Caprettini & Voth (2020) use adver-

tisements in 60 regional English newspapers from 1800-1830 to measure the spatial

diffusion of threshing machines, which they show contributed to the Swing Riots.

A related but slightly different use of newspaper data are studies where newspapers

are themselves a key mechanism through which treatment occurs. In the U.K., Beach

& Hanlon (Forthcoming) use newspapers as a way to measure variation in exposure to

news about a specific event, the Bradlaugh-Besant trial of 1877. They then analyze

9

Most of this literature uses newspapers to identify the existence of local interventions. Velde

(2022) is an interesting exception, as it leverages a reporting quirk wherein a strike in August of

1917 prompted San Francisco newspapers to start publishing weekly reports on daily public transit

revenues, a practice they continued for a number of years. Velde (2022) uses this information as

a proxy for economic activity and builds a model where individuals choose their level of economic

activity based on perceptions of infection risk.

13

how exposure to this trial affected fertility behavior. In Albright et al. (2021),

the authors show how exposure to newspaper coverage of the Tulsa Race Massacre

influenced homeownership and occupational standing. These studies highlight how

newspaper information can be used to measure a wide variety of treatment variables,

ranging from technology to public sentiment, including cases in which the newspaper

exposure itself is the treatment of interest.

Another use of newspaper data is to construct outcome variables of interest. Stud-

ies in this vein show how newspaper data can allow the measurement of outcomes

that are difficult to quantify through other means. This area includes two important

early studies. Rhode & Strumpf (2004) use newspaper data to evaluate the reliabil-

ity and efficiency of historical presidential betting markets.

10

That study spans an

important technological advancement for researchers, as the authors note that half

of their data was obtained from manual microfilm searches and the other half was

obtained from searches of machine-readable text on Proquest.com. Glaeser & Goldin

(2006) construct an index on reported corruption based on newspaper mentions of

“fraud” and “corruption,” which they use to make the point that corruption in the

United States started falling towards the end of the 19th century.

More recent studies in this vein include Beach et al. (2022), which uses a technique

similar to the one introduced by Glaeser & Goldin (2006) to map regional variation in

the arrival of the 1918 influenza pandemic and the intensity of discussions surrounding

non-pharmaceutical interventions. Masera & Rosenberg (2022) use historical U.S.

newspapers to study how changes in the importance of cotton in local agricultural

economies in the U.S. South affected support for slavery, as revealed in newspaper

articles. Some studies use newspapers to measure both treatment and outcomes.

10

See also their follow-up, Rhode & Strumpf (2013), which examines international markets.

14

Ang (2020) and Esposito et al. (2021), for example, both use newspapers to identify

screenings of The Birth of a Nation as well as to look at how these screenings impacted

public discourse, as reflected by local newspaper articles. In China, Zhang (2021) uses

searches of major urban newspapers to track the diffusion of political information

across the country in the early twentieth century.

Some studies construct outcome variables based on information from newspaper

advertisements. Lennon (2016) uses antebellum U.S. newspapers to show that the

Fugitive Slave Act led to both a reduction in the number of ads posted and rewards

offered by enslavers looking for “runaway slaves.” Rhode (2021) examines newspaper

advertisements to document the behavior of the market for cotton seeds in the U.S.

in the antebellum period. Another interesting use is Celerier & Tak (2021), which

compares the language used in ads posted by the Freedman’s Savings Bank relative

to other financial institutions that were advertising in the same newspaper. Other

recent papers, such as Gray & Bowman (2021) and Coury et al. (2022), use newspa-

pers to obtain real estate prices. Coury et al. (2022), for example, uses real estate

transactions listed in the Chicago Tribune to assess the impact of urban water and

sewer infrastructure investments on land values. These recent studies build on a long

line of work using newspapers to study historical housing markets, dating back at

least to Rees (1961).

11

News reports and the behavior of newspapers themselves are also, in some cases,

a primary object of interest. Much of the literature on newspaper behavior uses

directory data. Those studies are discussed in the next subsection. A smaller set

uses information from newspaper articles. Costa & Kahn (2017) examine how news

11

In ongoing work funded by the National Science Foundation, Rowena Gray, Ronan C. Lyons

and Allison Shertzer are digitizing similar data from a much larger set of papers to construct a

new long-run urban housing price series for a substantially broader set of U.S. cities than has been

available in previous work.

15

coverage of disease epidemics responded to actual changes in death rates, which helps

us better understand how the newspaper sector operated and shed light on the types

of information that people would have been exposed to through newspapers at any

given point in time. Wang (2019) examines how the introduction of electric telegraph

connections affected local political participation. He uses digitized newspaper data to

show that local newspapers increased their coverage of national political events, which

acted as a key mechanism through which better telegraph connections influenced

political participation. Ottinger & Winkler (2020) use newspapers to study how

political competition from the Populist Party in the years just after 1892 led the

Democratic party to spread more racist propaganda. One notable paper, Gentzkow

et al. (2011), uses a combination of directory data and searches in digitized newspaper

archives. We discuss that paper in more detail in the next subsection.

Finally, newspaper data may be used to augment or improve other data sets.

For example, newspaper information has been used to help generate more systematic

data on lynching in the U.S. (Cook, 2012). A particularly novel recent application

of historical newspaper data, by Ferrara et al. (2022), shows that measures of an

event derived from newspaper reports can be used as an instrument that improves

the precision of an outcome variable measured with noise. Their specific case uses

newspaper reports to track the spread of the Boll Weevil, an agricultural parasite

affecting cotton, through the U.S. South. The arrival of the Boll Weevil, as indicated

by a historical map produced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, has been used

to provide quasi-exogenous variation by several existing studies. Ferrara et al. (2022)

show that newspaper reports can provide an instrument that can help address mea-

surement error in the original map, resulting in increased precision. Another example

is provided by Lisa Cook (2011, 2014), where newspaper data is used in order to

16

identify African-American inventors in U.S. patent data. This allows her to study

factors that impacted the inventive output of African-Americans despite the fact that

race information is not included in the original patent data.

12

One theme to emerge from this review is that newspaper data are being used for

a wide range of different purposes, but in a small number of locations. This likely

reflects the fact that the U.S. and U.K. databases are the most extensive and, being

in English, the easiest for most researchers to access. However, we expect that over

time extensive databases will become available for a wider range of countries and

languages. A broadening of the set of contexts in which historical newspaper data

are studied is likely to be an important trend going forward.

3.2 Using newspaper directory data

A substantial set of studies use a different type of newspaper data: those obtained

from newspaper directories. As we discuss in the next section, rather than providing

the text of actual newspapers, directory data provide information about newspapers

as organizations. As a result, these data are particularly suited for studying changes

in the newspaper market. The directory data are not our primary object of interest

here, but because they are related to the digitized article data in important ways it

is useful to briefly review some of the recent literature using newspaper directories.

One important contribution to this literature is Gentzkow et al. (2011), which

uses directory data to examine how the entry of a new daily newspaper affects polit-

ical participation. They find that newspaper entry increases political participation,

particularly when it was the first daily newspaper and if it arrived prior to the in-

12

While patent data are the primary measure of inventive behavior, Cook (2014) also examines

the establishment of African-American newspapers as an alternative measure of productive activity

that was discouraged by racial violence.

17

troduction of radio and television. They also supplement their directory data with

additional text searches of articles in one digitized newspaper database, Newspa-

perArchive.com, which they use to study the political leaning of different papers.

Petrova (2011) uses directory data from the U.S. in the 1880s to identify a link be-

tween the amount of available advertising revenue in a location and the independence

of newspapers. Gentzkow et al. (2014a) use newspaper directory data, together with

additional information on newspaper circulation, to look at how competitive forces

affected newspapers’ ideological diversity. Gentzkow et al. (2015) examine newspa-

per entry, exit, circulation, and content following a change in party control. With

the exception of the South during Reconstruction, they find little evidence that news-

papers catered to the state during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Perlman

& Sprick Schuster (2016) use directory data to study the impact of rural free deliv-

ery by the U.S. Post Office on the behavior of voters and politicians. Using French

data, Cag´e (2020) studies how competition affects the quality and quantity of news

provided by local papers.

All of these studies demonstrate how useful newspaper directory data can be for

understanding media markets. However, as we argue below, newspaper directory data

can also serve a second helpful purpose: increasing the usefulness of data drawn from

digitized newspaper archives.

4 Data Sources

4.1 Digitized Historical Newspaper Archives

In this section, we review the primary sources of digitized historical newspaper data

and provide some analysis of the extent of their coverage. Most existing work within

18

economics has focused on data drawn from the U.S. or the U.K. and so we focus most

of our attention on those contexts.

13

All of the U.K. studies that we are aware of (e.g., Caprettini & Voth (2020), Beach

& Hanlon (Forthcoming)) use data from the extensive British Newspaper Archive, a

partnership between Findmypast and the British Library which makes use of the

latter’s extensive holdings. In contrast, studies focused on the U.S. draw on a variety

of sources, including Ancestry’s Newspapers.com, the Chronicling America database

from the Library of Congress, the Readex’s Early American Newspaper Archive,

NewspaperArchive.com, Proquest Historical Newspapers, Gale’s Nineteenth Century

Newspaper Archive, etc.

14

Newspapers.com, by far the most used database, is the

exclusive source for Ager et al. (Forthcoming), Albright et al. (2021), Bazzi et al.

(2021), Calderon et al. (Forthcoming), Esposito et al. (2021), Ferrara et al. (2022),

and Ottinger & Winkler (2020). These studies tend to focus on the late nineteenth

or early twentieth century. Ferrara & Fishback (Forthcoming) and Wang (2019)

use data from the Chronicling America database. Masera & Rosenberg (2022) uses

two sources, Chronicling America and the Gale Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspaper

Archive. Gentzkow et al. (2011) uses searches in NewspaperArchive.com. Fouka

(2019) uses the Proquest Historical Newspaper database. Lennon (2016), which also

focuses on the antebellum period, uses Newsbank’s American Historical Newspapers.

Rhode (2021) is a rare study that uses information from a wider variety of data

sets, including most of those described below, as well as additional information from

GenealogyBank.com. Two other studies that use multiple databases are Ang (2020)

and Feigenbaum & Gross (2021).

13

A useful guide to some available European digital newspaper databases can be found at: https:

//libguides.bgsu.edu/c.php?g=227439&p=1507130.

14

Two additional sources that have not been used by economists thus far, but may provide

coverage for locations that are not well represented in available archives, are https://www.

americanantiquarian.org/ and https://www.smalltownpapers.com/.

19

Given this variety, it would be useful for researchers to know how extensive the

databases are for a given point in time. Many databases provide lists or counts

of the number of newspapers included, but these are not very informative because

for many newspapers coverage is sporadic. To get a better sense of the extent of

the holdings of these archives, we have conducted searches for one ‘neutral’ word,

“monday,” which is likely to appear regularly in any newspaper (we have also checked

alternative neutral words, which all deliver similar results). Table 1 presents the

number of hits we obtain in each archive for various years, while Table 2 divides these

hits by the country’s population. These tables provide a snapshot of coverage, as

holdings are likely to expand over time. Nevertheless, these figures can be useful for

indicating the databases that have the most extensive, though not necessarily the

most representative, holdings at any point in time.

The holdings of UK newspapers in the British Newspaper Archives appear to be

fairly extensive until the inter-war period. In the U.S., the Readex database ap-

pears particularly strong in the early nineteenth century, while the Newspapers.com

database from Ancestry has the richest coverage starting in the middle of the nine-

teenth century. These figures, however, do not reveal the extent of coverage in the

databases, since we do not observe the actual number of newspapers present. For

that, we need newspaper directory data, which we discuss in the next section.

One type of paper that is often missing from these newspaper databases are those

major papers that continue to exist and maintain their own archives. Leading papers

such as The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal in the U.S., and The

Times, The Guardian, and The Economist in the U.K., are typically not found in

digitized newspaper databases. Instead, these papers generally maintain their own

archive of historical articles which must be accessed through a separate subscription

20

service, or in some cases through a major data provider. Hanlon (2015) uses data from

The Economist archive to track cotton prices in the nineteenth century. Coury et al.

(2022) uses data from the Chicago Tribute to obtain historical real estate transaction

prices. Olzak (2015) uses information from the New York Times archive to identify

ethnic or racial conflict events in the U.S. This source is also used by Kuziemko &

Washington (2018) to study the association between President Kennedy and Civil

Rights in the 1960s. Glaeser & Goldin (2006) also conducts searches of the New York

Times database, which they use to complement broader searches in Newspapers.com.

Another notable paper is Costa & Kahn (2017) which uses data from a set of leading

papers for different cities.

The fact that major national papers are often not present in broader archives is

important to keep in mind given the extensive influence that they exerted at differ-

ent points in time. Missing these papers is unlikely to be an important concern in

studies where newspapers are primarily providing spatial variation, which is true of

the vast majority of existing studies. However, using the archives of major national

newspapers is likely to be particularly valuable in settings where broader newspaper

databases are not available. A good example is provided by a recent paper by Zhang

(2021), which uses databases from four of the most important Chinese newspapers

to track reporting of revolutionary activity in the early twentieth century. Another

context where using the archives of major papers may be useful is in studies where the

aim is to construct a consistent time-series, such as the “corruption and fraud index”

generated by Glaeser & Goldin (2006). Unlike the broader newspaper databases, using

a single-paper database for this type of application ensures that time-series patterns

will not be driven by changes in the underlying sample of papers being searched.

Digitized historical newspaper databases exist outside of the U.S. and U.K, but

21

Table 1: Number of hits in different U.K. and U.S. newspaper databases

Newspaper database

British Newspaper Gale Proquest

Newspaper Newspapers Readex archive Chronic. 19th Historical

Archive .com .com America Century Newspapers

Decade: (UK) (USA) (USA) (USA) (USA) (USA) (USA)

1700 33 124 155

1710 518 368 676

1720 3,183 1,637 1,536

1730 6,655 3,644 3,252 114

1740 8,734 5,382 3,769 15

1750 13,343 9,990 8,273 1,048

1760 26,528 21,326 22,451 1,892

1770 51,764 25,339 29,669 2,799

1780 81,391 33,469 70,205 2,119 105

1790 89,035 53,789 217,568 12,472 5,032 1,337

1800 264,127 101,523 359,614 18,569 11,549 6,552 2,525

1810 364,984 127,844 545,684 32,583 13,621 15,150 2,198

1820 708,789 197,016 585,235 67,896 21,260 51,239 13,043

1830 1,348,109 352,802 524,751 131,315 35,402 83,232 27,112

1840 2,082,731 663,659 668,375 243,830 111,404 171,217 78,881

1850 3,019,594 1,171,442 931,864 534,514 261,340 187,680 160,471

1860 4,905,386 1,753,846 1,271,369 704,603 370,404 233,797 227,144

1870 4,928,997 2,752,428 1,567,505 1,167,003 523,462 344,798 297,138

1880 6,637,588 4,980,174 1,251,730 1,854,728 744,174 452,599 378,243

1890 7,248,636 8,684,995 2,052,415 3,365,648 1,324,338 576,865

1900 7,498,009 13,008,301 2,754,353 5,112,987 1,956,051 729,198

1910 5,294,361 16,615,927 3,757,185 6,441,053 2,241,731 773,090

1920 4,056,658 17,683,204 3,631,978 6,639,430 930,759 981,667

1930 4,511,409 18,977,845 3,371,899 6,675,158 307,170 1,204,557

1940 2,750,272 19,145,907 3,686,220 6,879,242 293,350 1,107,116

1950 2,406,907 26,263,984 5,886,327 10,739,657 234,197 1,458,975

Each cell presents the number of hits for the search term “monday” in each decade starting with

the indicated year (so 1700 indicates a search spanning January 1, 1700 to December 31, 1709).

These queries were conducted in April of 2022.

22

Table 2: Hits per thousand persons in different U.K. and U.S. newspaper databases

Newspaper database

British Newspaper Gale Proquest

Newspaper Newspapers Readex archive Chronic. 19th Historical

Archive .com .com America Century Newspapers

Decade: (UK) (USA) (USA) (USA) (USA) (USA) (USA)

1800 26 19 68 3 2 1 0

1810 31 18 75 5 2 2 0

1820 48 20 61 7 2 5 1

1830 75 27 41 10 3 6 2

1840 97 39 39 14 7 10 5

1850 116 51 40 23 11 8 7

1860 174 56 40 22 12 7 7

1870 161 71 41 30 14 9 8

1880 188 99 25 37 15 9 8

1890 188 138 33 53 21 0 9

1900 179 171 36 67 26 0 10

1910 113 180 41 70 24 0 8

1920 86 167 34 63 9 0 9

1930 91 154 27 54 2 0 10

1940 N/A 145 28 52 2 0 8

1950 43 174 39 71 2 0 10

Each cell presents the number of hits for the search term “monday” in each decade starting with

the indicated year (so 1700 indicates a search spanning January 1, 1700 to December 31, 1709)

divided by the census population at the beginning of that decade. For the British Newspaper

Archive, we use only hits from England and Wales, which is somewhat lower than the numbers

shown in Figure 1 (which includes all of the U.K.), divided by the population for England and

Wales. Since no census was completed in 1941, we do not provide an observation for that year.

These queries were conducted in April of 2022.

23

thus far these have not been extensively used. Many of these come from major data

providers, such as Gale and Proquest, and are available through university libraries. A

brief review of these resources suggests that current holdings remain relatively sparse

for many contexts, particularly in developing countries, though these databases are

likely to grow in the future. There are also likely to be rich databases for particular

contexts provided by individual libraries, archives, or other institutions. A good

example of this is the set of digitized Francophone Canadian Newspapers provided

by the Bibliotheque et Archives National du Quebec.

4.2 Mining digitized newspaper databases

What type of data are studies extracting from historical newspaper databases? While

digitized historical newspapers contain a wealth of information, the extent to which

this information can be extracted and utilized is often limited by the system though

which it is accessed. Of the digitized newspaper databases that we are aware of,

only one, the Chronicling America database from the Library of Congress, allows

researchers to download the underlying article data (though in some cases it may be

possible to access full-text data from other databases using web-scraping techniques).

The other databases must be accessed using the search portal provided by the data

provider. As a result, most studies in this area have taken a keyword approach where

they search for just one or a few keywords (e.g., “lynch” or “Boll Weevil”) that allow

them to identify particular types of events. In some cases, the number of search hits

is the key variable taken from the newspaper data, while in other cases searches for

particular key words are used to identify articles that are then manually reviewed to

obtain the needed information. The latter approach represents a much more labor

intensive process, which probably explains why this is the less common of the two.

24

The exact types of searches that can be conducted, and the types of outcomes that

they generate, will depend on the structure of the search portal through which the

articles are accessed. Search functionality varies in important ways across databases.

For example, the Chronicling America database, offers a fairly sophisticated search

portal that has options such as searching for two words within a specific proximity

(number of words) of one another. It also allows searches focusing only on the front

page of the paper. However, it does not appear to offer to possibility of running

searches with wildcard characters (“*”). In contrast, the Newspapers.com search

portal allows the use of wildcards, a functionality that seems to be rare in the other

databases we have examined. In some other cases, a search term is treated as a

stem word, and so a search for “honest” will return results for honest, honesty but

also dishonest and dishonesty. Because search functionality varies across databases,

there may be applications where researchers will be better off using a less extensive

newspaper archive if it offers particular advantages in terms of search functionality.

There are also important differences in how the search function operates. In the

British Newspaper Archive, for example, searches focus on articles. So, a search for

two keywords will pick up a hit only if both appear in the same article. This is not

true for some of the other databases. In Newspapers.com, for example, the search

applies across the full page of the paper. So a search for “monday” and “Deschutes”

will identify pages where these two terms appear anywhere on the same page. The

same is true for Chronicling America, but the possibility of limiting a search to words

appearing within a certain proximity can be used to partially address this tendency.

Differences in the available search functions and the search approach offered by

each database can have important impacts on the types of results generated. We

recommend that researchers pay close attention to these differences when choosing a

25

database to use in contexts where more than one are available.

4.3 Newspaper Directories

Newspaper directories can be an extremely valuable tool when used together with

digitized historical newspaper article datasets. These directories were produced by

private publishers with the purpose of connecting advertisers with newspapers. The

systematic publication of newspaper directories began in 1846, with Mitchell’s News-

paper Press Directory, though lists of newspapers had been published on a more ad

hoc basis before that point. Originally focused on just U.K. newspapers, Mitchell’s

directory was expanded to include magazines and other periodicals in 1860, continen-

tal papers in 1878, and American papers in 1880.

15

A colonial supplement began in

1885. Other directories soon followed, such as Rowell’s American Newspaper Direc-

tory or the N.W. Ayer and Son’s Newspaper Annual Directory, both focused on the

U.S. Scanned versions of numerous years of these directories can be found on websites

such as Hathitrust and Google Books, though digitized versions remain sparse.

16

An example entry from Mitchell’s 1847 directory is presented in Figure 1. This

shows the type of information typically provided by a directory, including newspaper

name, frequency of publication, price, date of establishment, political stance and

some details about the types of news included, and the publisher name and location.

While the information included varies somewhat across directories, most include these

details. Some directories include information related to circulation, in some cases just

through listing circulation areas. However, since circulation figures were likely self-

reported and hard to verify, that information may be exaggerated.

15

Gliserman (1969).

16

The Library of Congress provides links to scanned copies of many of these directories at these

URLs: https://www.loc.gov/rr/news/news_research_tools/ayersdirectory.html; https://

26

Figure 1: An example from the 1847 Newspaper Press Directory

Complete or partial digitization of newspaper press directories are available from

a number of sources. Gentzkow et al. (2014b) have digitized the daily newspaper

entries from U.S. directories in 1869 and every presidential year spanning 1872 to

2004. Non-daily entries for the 11 former Confederate States of America in 1869 and

every presidential election spanning 1872 to 1896 are available from Gentzkow et al.

(2014c). For this article, we have digitized a complete set of directory data for the

U.S. for 1910, including all papers. In earlier work, we digitized U.K. directory data

for 1895, including only papers outside of London (Beach & Hanlon, Forthcoming).

Both of these transcriptions are available in the replication package for this article.

There are some alternatives to newspaper press directories that provide similar

types of information. The most promising source, particularly in the period before the

existence of press directories, is government documents. Wang (2019), for example,

uses a listing of newspapers produced as part of the 1840 U.S. Census of Manufactures.

Government sources are also likely to be valuable in more recent time periods. Cag´e

(2020), for example, uses a mix of government and other sources to construct listings

memory.loc.gov/diglib/vols/loc.gdc.sr.sn91012092/default.html.

27

Table 3: Frequency and politics of papers in the 1895 U.K. Newspaper Directory

Frequency Count Politics Count

Daily (4+ times per week) 136 Conservative 328

Weekly (1-3 times per week) 1,282 Liberal 409

Other/unknown 61 Independent 298

Neutral 244

Other/Unknown 200

Total 1,479 Total 1,479

of French newspapers starting in 1944. Other sources are likely to exist given that

newspapers were heavily taxed in many countries before the twentieth century. These

sources are likely to be particularly valuable when they are available for periods or

locations for which press directories are not available.

4.4 Evaluating Available Databases

One of the benefits of using newspaper directory data is that they allow us to evaluate

the coverage and selection of existing digitized newspaper archives. In this section, our

points of reference include Mitchell’s directory for 1895, which includes newspapers

outside of London, and a directory of U.S. newspapers from Ayer & Son’s for 1910.

Table 3 provides some basic statistics for the 1895 UK Directory. We observe

nearly 1,500 total papers active in England & Wales in this year. About 86% of the

papers were published once, twice, or thrice weekly and another 9% can be called

dailies (published 4-7 days a week). In terms of politics, we see a fairly even balance

between Conservative and Liberal-leaning papers and a substantial number of polit-

ically Independent or neutral papers. The latter group often includes those with a

non-political focus, such as trade and commercial papers, local advertisers, etc.

28

Table 4: Frequency, type and pricing of papers in the 1910 U.S. Newspaper Directory

Frequency Count Type Count Cost Count Other feat. Count

Daily (4+ per week) 2,376 Republican 6,502 Below one 1,636 Black 305

Weekly (1-3 p.w.) 16,447 Democrat 4,933 One dollar 10,698 (share) 0.014

Other/unknown 3,698 Independent 3,701 One to two 4,475

Trade/bus. 1,664 Two dollars 1,844 Foreign lang. 1,034

Religious 826 Above two 3,202 (share) 0.046

Other/unk. 4,893

Total 22,519 22,521 22,521

Table 4 present similar statistics drawn from the 1910 U.S. directory, with ad-

ditional details on the breakdown by subscription prices. While we see many daily

papers in this directory, the list is still dominated by weekly papers. Republican pa-

pers outnumber Democratic and Independent ones ones. There are also quite a few

papers focused on trade and business or for particular religious groups. The modal

subscription price was one dollar, though daily papers tended to be more expensive

because a subscription included more issues. A small number of papers, 1.4%, were

tailored to a Black audience and 4.6% of papers were published in a foreign language.

The directory data can be used to gain a sense of the coverage available in the

digitized newspaper article databases for these periods and locations. For the U.K.,

we evaluate coverage in the British Newspaper Archive in 1895 compared to the di-

rectory data from that year. For the U.S., we focus on the Newspapers.com and

NewspaperArchive.com, the two sources with the most holdings in 1910, which we

compare to the U.S. directory data for a selection of states. To undertake our com-

parisons, we search the newspaper article databases looking for any mentions of the

term “monday” during the year. We then manually match every paper that shows

up in the search to the corresponding paper in the directory data. Our assumption

here is that any paper with a meaningful presence in the archive database in the year

29

Table 5: Coverage of English and Welsh papers in the British Newspaper Archive

Searching for “Monday” Searching for “Rain”

All papers Dailies Weeklies All papers Dailies Weeklies

Total 1479 136 1282 1479 136 1282

In BNA 449 64 377 448 64 376

Coverage rate 0.303 0.471 0.294 0.302 0.471 0.293

Queries conducted May 2022 to see which newspapers appear at least once in the BNA database

for the year 1895.

will use the word “monday” at least once, even if the paper itself is not published

on Mondays. As a check, in the British data we also consider a second search term,

“rain”, a perennial item of discussion among the British population.

Table 5 describes the rate of coverage of English and Welsh papers (outside of

London) in the British Newspaper Archive (BNA) in 1895. In the first three columns,

we identify newspapers in the BNA by searching for “monday” anytime during the

year. In the next three columns we instead search for “rain”. Both approaches give

nearly identical results, so it is clear that the choice of search term is not an important

factor in our results.

Roughly 30% of papers active in England & Wales (excluding London) in 1895

appear in the BNA. Coverage is a bit higher (around 47%) for daily papers, which were

mainly located in cities or larger towns than for weekly papers (29%). Overall, the

BNA covers a substantial fraction of the total set of papers, but still there are many,

even among the daily papers, that do not appear in the dataset. One implication of

this fact is that there is substantial room for selection concerns, an issue that we will

return to later.

Table 6 provides a similar set of statistics for a set of U.S. states, chosen to

30

Table 6: Coverage of papers in a selection of U.S. states in 1910

All papers Dailies

Alab. Mass. Nebr. Wash. Alab. Mass. Nebr. Wash.

Papers present 253 688 627 371 26 83 29 33

Newspapers.com 90 14 434 32 8 8 23 11

Coverage rate 0.36 0.02 0.69 0.09 0.31 0.10 0.79 0.33

NewspaperArchive 7 17 35 22 3 6 5 6

Coverage rate 0.03 0.02 0.06 0.06 0.12 0.07 0.17 0.18

Combined 94 25 436 36 10 11 24 12

Coverage rate 0.37 0.04 0.70 0.10 0.38 0.13 0.83 0.36

represent each region of the country.

17

We present results for the two databases

that had the largest holdings for that period based on the results shown in Table

1, Newspapers.com and NewspaperArchive.com. The final rows of Table 6 present

results after pooling information from the two databases. The first takeaway is that

coverage varies dramatically across states. In Nebraska, a majority of the papers

listed in the directory are also found on Newspapers.com. Coverage in Nebraska is

even better if we exclude the two major cities, Omaha and Lincoln, which had a wider

variety of specialty papers that are less likely to show up in the database. Excluding

these two major cities, 75% of all papers are covered and 90% of dailies. At the other

extreme, only 2% of Massachusetts newspapers appear in either dataset. The second

takeaway is that there is substantial overlap in terms of the set of papers covered by

the two databases, as the gains in coverage from combining information from the two

sources are fairly modest.

17

Covering all states is somewhat infeasible due to the size of the U.S. newspaper market and the

fact that matching database search results to the directory must be done manually

31

The discussion thus far has focused on how historical newspaper database coverage

compares at a given point in time, but it is also worth thinking about how changes in

database coverage over time might impact results. Newspaper databases change along

two predictable margins. The first margin concerns the set of newspapers and issues

that are included in the database. While we tend to appreciate that the collections are

constantly expanding, we lack a complete understanding of how this process changes

the composition of the underlying data. Expansions likely shift the geographic and

periodic focus in discrete ways as archives become discovered and digitized. The

second margin concerns the contextual information, which changes as improvements

in OCR and scanning technology make content analysis more reliable, and in some

cases, as that technology allows for more sophisticated searches.

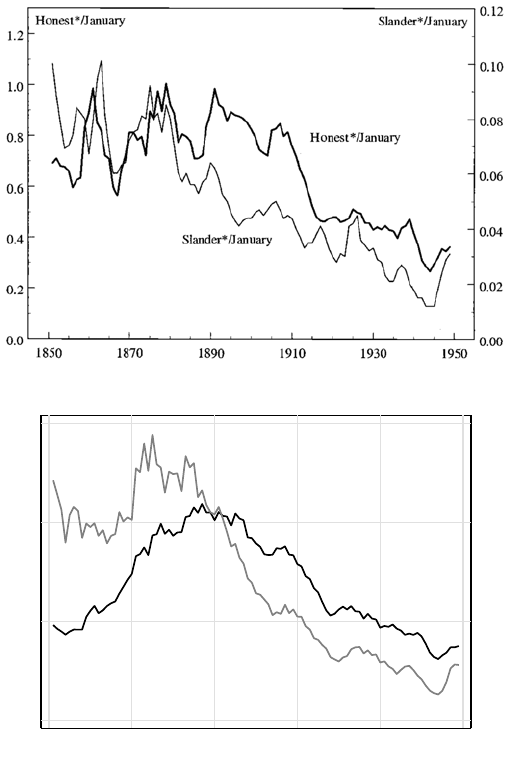

We provide insight on these issues by replicating a result from Gentzkow et al.

(2006). In that chapter, the authors conducted keyword searches to provide evi-

dence that the use of charged language in U.S. newspapers starts declining some-

where between 1870 and 1920. We focus on this result because it is one of the

earliest papers that uses digitized newspaper databases to measure long-run trends

and the transparency of its presentation allows for a useful visual comparison of how

and where coverage may have changed. In 2004, those authors conducted keyword

searches for “Honest*”, “Slander*”, and “January,” on Ancestry.com, before Ancestry

started marketing its newspaper materials as a separate subscription service (News-

papers.com). The authors deflate each stem word (Honest and Slander) by January

and plot three-year moving averages of those two indices. The top panel of Figure 2

reprints that result.

To see how changes in the coverage of newspapers within the same database over

time can affect results, we replicate their exercise (as of May 2022 and using News-

32

papers.com) and plot those results in the bottom panel of Figure 2. One takeaway

from this comparison is that the 2022 query results show much less volatility than the

2004 query results, particularly in the 19th century. Another takeaway is that, while

there are important similarities in the patterns we observe, such as the consistent de-

cline in the use of both “honest” and “slander” after 1890, there are also meaningful

differences. The most notable of these is the increase in the use of these terms in the

1860s and 1870s, which appears clearly in the 2022 results but not in the 2004 query.

One implication of this exercise is that changes over time in the content of news-

paper databases can have a meaningful impact on results, though this concern will

continue to diminish as coverage expands. Some caution may be warranted when

using newspaper databases to evaluate long-run patterns because of the potential for

compositional changes to influence results. One solution, which is one that Glaeser

& Goldin (2006) implement, is to present results from a subset of newspapers that

don’t enter or exit the sample over time. This appears computationally difficult, but

not impossible, to apply at scale.

33

Figure 2: Trends in Biased Reporting Over Time and By Date of Search Query

2004 Query Results (Gentzkow, Glaeser, and Goldin)

2022 Query Results (Beach and Hanlon)

Honest*/January

Honest*/January

Slander*/January

Slander*/January

0

.04

.08

.12

0

.4

.8

1.2

1850 1870 1890 1910 1930 1950

Year

Notes: Lines represent three-year moving averages. Gentzkow, Glaeser, and Goldin queries con-

ducted on Ancestry.com in 2004. Beach and Hanlon queries conducted in May of 2022 using News-

papers.com, which is marketed as a separate subscription service by Ancestry.com.

5 Data Challenges

The central challenge in using digitized historical newspaper data is in dealing with

the fact that only a fraction of newspaper articles make it into one of the available

34

database. This fraction is growing as extant archives are digitized. However, many

newspapers and articles no longer exist and will thus remain missing from these

databases. This section discusses this issue and suggests some possible solutions.

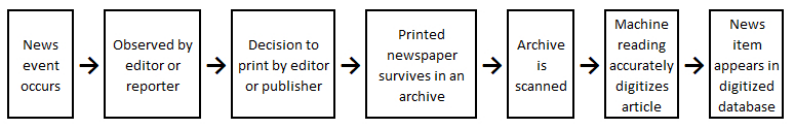

It is useful to start by thinking about the process through which a news item (or

advertisement, letter to the editor, etc.) must pass through in order to be present

in a digitized newspaper dataset. This progression is described in Figure 3. Most

digitized newspaper data start as a news item, though some may originate as an

opinion piece, advertisement, letter to the editor, or some other form of newspaper

content. Some subset of news items are observed by newspapers, either through a

reporter or some other means.

18

Some subset of these are printed, a decision that

may depend on the type of person in control of the paper, the target audience, and

the type of environment in which the paper operates. Because whether a news item

or other piece of content makes it in to print will depend on the way that newspapers

are collecting information (e.g., whether they rely on other sources or do their own

reporting) as well as the choices made by the editor or publisher in charge of the

paper, selection at this stage will depend crucially on the structure of newspapers

and the media market. This is why obtaining a basic understanding of these features

in any historical context is likely to be important for designing an analysis strategy.

19

Of the content that is printed, only a subset will survive to be included in a

modern newspaper archive. This is another crucial point at which selection is likely

to matter. Papers written for less prominent groups, such as working class readers

18

Perhaps the most famous newspaper article based on “unobserved” information was the Chicago

Daily Tribune’s incorrect printing of the November 3, 1948 headline “DEWEY DEFEATS TRU-

MAN,” which was written with the expectation that Dewey would win the presidency, as conven-

tional wisdom and various polls were predicting a landslide victory for Dewey.

19

It is also important for the researcher to understand other historical nuances that affect which

articles make it to print. For instance, it is often asserted that censorship of the press led to an

underreporting of influenza deaths, particularly deaths of soldiers, during 1918. This is unlikely to be

the only situation where sensitive information was discouraged from being discussed by newspapers.

35

or minority groups, those published in smaller towns, and certainly those that did

not pay stamp taxes, are less likely to have been archived than prominent national

or regional papers of record. This selection, particularly because it is unlikely to be

random, may have implications for some analysis strategies. Even when a paper is

archived, and then scanned into a digital database, the extent to which the content

is accurately machine read is also likely to vary with features such as the level of

printing quality or the type font used.

Only after passing through all of these various stages does a news item appear as

a potentially usable datum in a searchable newspaper database. Not every step along

this path presents a challenge for every analysis strategy, but it is useful to keep these

various stages in mind when evaluating any particular approach.

Figure 3: From news to data

We can get a sense of the extent and nature of selection present in our sample

of historical newspaper data by comparing the set of papers covered to the paper

characteristics identified in the directory data. In Table 7, we examine selection

within the set of English and Welsh newspapers in 1895, focusing only on weekly and

daily papers. Daily papers and more established papers were more likely to appear in

the BNA archive. The correlations with party affiliation are small but too imprecise

to draw strong conclusions.

Selection looks somewhat different in the U.S. context, which is examined in Table

8, where we focus on inclusion in the Newspapers.com archive. Affiliation with one

36

Table 7: Predictors of newspaper presence in BNA archive in 1895

DV: Paper appears in BNA archive

(1) (2) (3)

Daily 0.160

∗∗∗

0.158

∗∗∗

0.165

∗∗∗

(0.046) (0.046) (0.044)

Conservative 0.037 0.007

(0.047) (0.045)

Liberal 0.053 0.029

(0.046) (0.044)

Independent 0.026 0.036

(0.048) (0.046)

Neutral 0.039 0.060

(0.050) (0.048)

Years Since Est. 0.004

∗∗∗

(0.000)

Observations 1362 1362 1362

R-squared 0.010 0.011 0.075

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Robust

standard errors in parentheses. Coefficients

come from a linear probability model.

37

of the major political parties is a strong predictor of whether a paper appears in the

digital archive. This effect is particularly strong in Alabama, the only Southern state

in the sample. Older papers, which were likely to be more established, were also more

likely to appear. In contrast, Black papers, trade papers, and religious papers were

relatively less likely to be found in the archive. Papers published in foreign languages

are also less likely to show up in our search, but this is not unexpected given our

approach. It is somewhat surprising that daily papers were not more likely to appear

in the archive, given that these tended to be more established papers located in

larger towns and cities. Overall, there is plenty of evidence here that selection into

coverage was non-random, though the type of selection indicated by these results will

not necessarily create issues for every type of study. Scholars focused on politics,

for example, may be comforted by the fact that the probability that Republican and

Democratic papers are included does not appear to be significantly different, at least

on those states where there is enough coverage to identify clear patterns.

The results above highlight a central challenge in using digitized historical news-

paper data; not only did only a fraction of newspapers survive to make it into modern

newspaper databases, but this group appears to have been selected along dimensions

that may have an important impact on research strategies. Next, we discuss some

approaches that can help researchers ameliorate these concerns.

One straightforward use of historical newspaper databases is to compare the spa-

tial or temporal distribution of some type of data hit, say a news report including

the word stem “lynch”, to some other variable. Naturally, the spatial and temporal

variation of these hits is likely to be heavily influenced by the underlying set of papers

in the database used. This will introduce selection bias is a newspapers presence in

the database is influenced by any factor that may also be related to the comparison

38

Table 8: Predictors of US newspaper in Newspapers.com in 1910

DV: Paper appears in Newspapers.com

By State

AL MA NE WA

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

Daily -0.125

∗∗∗

-0.175

∗

0.063

∗

0.070 0.264

∗∗∗

(0.038) (0.104) (0.033) (0.063) (0.085)

Democratic 0.229

∗∗∗

0.342

∗∗∗

0.015 0.106 0.113

(0.041) (0.085) (0.037) (0.065) (0.112)

Republican 0.165

∗∗∗

0.306

∗

0.069

∗∗∗

0.151

∗∗∗

-0.055

(0.036) (0.166) (0.026) (0.053) (0.040)

Independent 0.023 -0.011 -0.001 0.074 -0.020

(0.038) (0.106) (0.014) (0.063) (0.044)

Trade/Bus. -0.299

∗∗∗

-0.108

∗

-0.010 -0.696

∗∗∗

-0.076

∗∗

(0.029) (0.064) (0.007) (0.051) (0.037)

Religious -0.282

∗∗∗

-0.121

∗∗

-0.021 -0.490

∗∗∗

-0.076

(0.030) (0.058) (0.013) (0.165) (0.053)